Daniel Schönfelder is a lawyer and lecturer in BHR. He recently co-authored the first handbook on the new German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act.

Bettina Braun is a policy advisor at the German Institute for Human Rights. There, she works in the business and human rights team, focusing on legislative developments in the EU and worldwide. She previously worked on business and human rights developments and corporate accountability issues with civil society organizations in the US. She holds an LL.M. from Columbia law school and received her first law degree from the University of Bonn, Germany.

Martijn Scheltema is partner of Pels Rijcken and member of the Dutch Supreme Court Bar since 1997. He has specialized in business and human rights and climate change issues. He has been involved in the Srebrenica, SNS expropriation, Urgenda and Shell Kiobel cases. He chairs the business and human rights practice group of his firm and the independent binding dispute resolution mechanism of the Dutch Responsible Business Conduct agreement in the Textile and Natural Stone sectors. He is professor at Erasmus University Rotterdam and researches business human rights and climate change related issues. He has advised the Dutch State Department on legislative options in the business human rights arena.

I. Introduction and relevance of contractual mechanisms

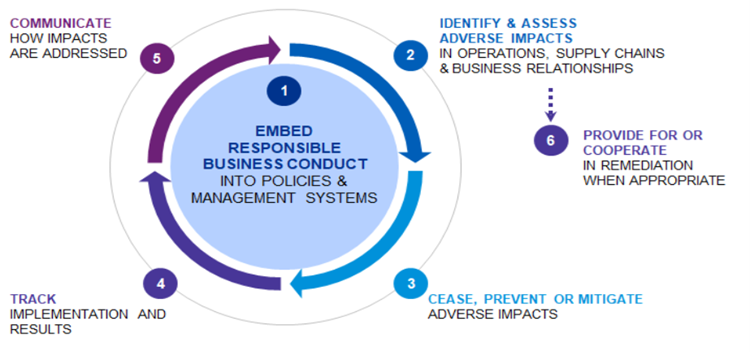

Contracts are regularly employed to address human rights and environmental (HRE) issues that arise in supply chains. Buying companies often have Supplier Codes of Conduct that cover matters related to HRE protection and use contracts to attempt to secure supplier compliance with these codes of conduct.[1] Many buyers, mainly western brands, consider contracts to be an important tool in carrying out HRE due diligence,[2] as envisaged by the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidance on Due Diligence for Responsible Business Conduct.[3] This type of due diligence, which focusses on the risks business operations pose for external stakeholders, is summarized in the following graph:[4]

As the risk identification, prevention and mitigation required by this type of due diligence extends beyond the buyer’s own business operations to include supply chains, buyers have to ensure that their suppliers and sub-suppliers respect HRE standards. Contractual mechanisms play an important role here. This is reflected by current and proposed legislation, which will be discussed below and relies heavily on contractual assurances in supply chains.[5]

As the risk identification, prevention and mitigation required by this type of due diligence extends beyond the buyer’s own business operations to include supply chains, buyers have to ensure that their suppliers and sub-suppliers respect HRE standards. Contractual mechanisms play an important role here. This is reflected by current and proposed legislation, which will be discussed below and relies heavily on contractual assurances in supply chains.[5]

This contribution first analyzes current contractual practice, and why it fails to deliver effective human rights outcomes. It then presents a new approach in Model Contract Clauses of the American Bar Association (ABA MCCs 2.0), which aims to create obligations for both suppliers and buyers, promising more effective outcomes of due diligence efforts. The post then discusses how new legal obligations in Germany and possibly the EU shape requirements on contracting and closes with an outlook on European developments in this sphere, specifically the project to propose European Model Clauses.

II. Why current contractual practices are often not productive

Although contract clauses and Supplier Codes of Conduct that address human rights are frequent in practice, HRE impacts in supply chains persist.[6] One reason are frequent imbalances in negotiating power between the buying companies and the suppliers. Many suppliers depend on a very limited number of buying companies,[7] while, particularly in less specialized industries, it is easy for the buying company to swap suppliers, creating a race to the bottom of suppliers competing on ever lower social and human rights standards.[8] In this position, buyers frequently exert extreme price pressure, to the extent that many suppliers have reported taking orders at prices which would not even cover production costs.[9] Additionally, lead times are often too short, or buyers change or cancel orders last-minute. Through these practices, suppliers might not be able to pay living or even minimum wages, turn to undeclared work, and demand (unpaid) overtime.[10] However, current contractual mechanisms do not include obligations to source responsibly or engage in responsible purchasing practices; therefore, they often fail to adequately respond to the root causes of HRE problems. Additionally, it is not productive to put all costs of complying and verifying the implementation of the Supplier Codes of Conduct on suppliers, who might simply not be able to carry them if the buying companies do not address pricing.[11]

Another reason is that companies which use codes of conduct typically use them to shift the risk of HRE violations in the production process to the supplier by asking the supplier to guarantee that all work is carried out in accordance with the code. This fails to consider that HRE violations are endemic, so a supplier guarantee that they never occur or never will occur is unrealistic. Not only does such an approach fail to productively address root causes, but suppliers are also unlikely to report violations and proactively address them for fear of reprisal. At the same time, Supplier Codes of Conduct vary widely, which means that suppliers who work with multiple buyers can be subject to differing standards.

Even if Supplier Codes of Conduct do exist, companies do not necessarily monitor compliance with and enforce them in a way that leads to better human rights outcomes. Companies that do attempt to monitor and enforce their supplier codes usually do so via third-party audits. However, audits tend to be poor tools for detecting human rights violations, either because of their execution (e.g., interviewing workers in front of their employer), audit-fraud, or because human rights issues such as gender-based violence, chronic unpaid over-time, harassment and discrimination are difficult to detect.[12]

Some companies terminate contracts after a breach, which often does not solve the human rights issue. On the contrary, it might even cause the issue to worsen, since termination might force a supplier to contract other buyers who might be more lenient on these issues. For example, termination based on the use of child labour hardly improves the situation as long as the families need this in order to secure their livelihood. This behavior is contrary to principles of responsible disengagement in the UN Guiding Principles of Business and Human Rights and OECD Guidelines.[13]

Thus, contracts would be more effective in delivering better HRE outcomes if they include the responsibilities of both buyers and suppliers, if content and implementation became more uniform to avoid differing standards, and if the enforcement of the obligations focused on the HRE impact. Such enforcement should include assessments of supplier performance and ensure that buyer has access to information regarding this performance, as well as to information gathered through grievance mechanisms implemented by the supplier, building a dialogue and collaboration with this supplier, capacity building, more effective enforcement mechanisms than instant termination, as well as building better dispute resolution mechanisms.[14]

III. Short description of the ABA`s Model Contract Clauses (MCCs)

In an attempt to address these issues, the working group of the American Bar Association developed Model Contract Clauses to Protect Workers in Supply Chains.[15] These model clauses (MCCs) set forth a major shift in contract design, reflecting both recent research and thinking about what organizational strategies are most effective and recent and ongoing legislative developments, including not only US legislation but also the likely mandatory human rights due diligence law in the European Union. Instead of a typical regime of representations and warranties, with concomitant strict contractual liability, these clauses provide for a regime of human rights due diligence, requiring the parties to take appropriate steps to identify and address adverse human rights impacts. As a result, suppliers are less incentivized to hide problems for fear of contractual sanctions: they do not have to pretend that no human rights problems exist, but they have to show that they are implementing measures to address them.

Perhaps the most significant shift in the MCCs 2.0 is that buyers share contractual responsibility for human rights with their suppliers and sub‐suppliers. The supplier is obliged to enact principles of responsible sourcing and purchasing to avoid contributing to adverse human rights impacts, for example, by setting prices in collaboration with the supplier—rather than simply imposing prices unilaterally—to reach a price that allows the supplier to pay adequate wages, see Art. 1.3.[16] If a human rights violation occurs, and if the buying company contributed to it by engaging in irresponsible purchasing practices, then human rights remediation must be provided by both buyer and supplier to the extent of their respective contribution to the harm, Art. 2.3 e).[17]

This is the best way to integrate responsible purchasing as required by HRE due diligence. Merely changing purchasing practices via internal guidelines without contractually giving the supplier rights to enforce this lacks effectiveness as the supplier would be reluctant to address human rights problems caused for his workers in a dialogue with the buyer to find solutions: the supplier would have to fear being contractually castigated for not respecting the human rights of his workers. Concrete obligations of buying companies in the contract give suppliers some leverage and assurance to proactively and collaboratively address problems.

In order to address human rights issues throughout the entire supply chain, the MCCs include an obligation for the Supplier to ensure that their Suppliers and Sub suppliers implement human rights due diligence requirements, Art. 1.2 in their contracts (cascading obligations). The MCCs also stress the importance of providing remedy to those harmed in case of a breach, rather than merely using typical contractual remedies such as money damages that only benefit the contracting parties. In developing and implementing remediation (or corrective action) plans, suppliers (and buyers if they contributed to the harm) must consult with the affected stakeholders. Lastly, before terminating a contract—for whatever reason—buyers must “consider the potential adverse human rights impacts and employ commercially reasonable efforts to avoid or mitigate them”, Art. 1.3 f.

IV. Relevance of contractual provisions in HREDD legislation

Recent legislative initiatives on mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence legislation have picked up the practice of using contractual mechanisms to address violations in business relationships, potentially influencing if and how companies use them.

1) German supply chain due diligence act (GSCDDA)

The GSCDDA obliges companies to implement environmental and human rights due diligence steps, inspired by the UNGP and OECD Guidance.[18] A central element is the obligation to implement contractual provisions.[19] Another fundamental element is the obligation for the companies covered by the law to avoid contributing to human rights and environmental risks through their own operations, especially their purchasing.[20]

The GSCDDA`s requirements on contracts

As part of an obligation to prevent human rights risks, companies must ensure that suppliers provide contractual assurances of compliance with human rights and environmental standards covered by the GSCDDA.[21] This enables the company to take action vis-à-vis a direct supplier in the event of an environmental or human rights violation. Under Section 6 para. 4 no. 2, the contractual assurances must adequately address issues not only with direct suppliers but throughout the supply chain. This creates a lever to influence the tier- n suppliers for the company. Companies falling under the scope of the GSCDDA must ensure that direct suppliers are trained about the issues. This might include, for example, training on the priority risks and measures to minimize them.

The contract must establish control mechanisms, Sect. 6 para. 4 no. 4 to ensure compliance and companies must carry them out on a risk-based basis. The risk-based implementation must be based on an adequacy criteria[22]. Serious and particularly likely risks must be reviewed as a matter of priority. The explanatory memorandum mentions audits and certifications as instruments. Though contractually defined sanction mechanisms are not expressly required, they are likely required under the “effectiveness” requirement, and the government’s explanatory memorandum suggests that contractual penalties should be a component of corrective action plans.[23]

The provision on the termination of business in certain circumstances in Sect. 7 para 3 suggests the necessity of provisions on termination rights and milder means such as the suspension of business.[24] When terminating a business relationship before the contract expires, the negative human rights impact is to be taken into account, as a negative human rights impact arising of an exit is one that the company at least contributed to and needs to address through preventive measures under Section 6 Parr. 1, 4 Parr. 2 in its HRDD.[25]

Unless companies decide to negotiate the necessary contractual clauses for the implementation of the GSCDDA individually with each supplier, which seems rather impractical except in special cases, these clauses will be general terms and conditions (GTC) in accordance with Section 305 ff. of the German Civil Code. This will likely influence implementation and content of the clauses since these contractual conditions are subject to special requirements in order to protect the other party, i.a.: They may not be included in a surprising position in the contract, Section 305 c parr. 1. The GTC must be determined enough, i.e. clearly define the requirements the counterpart must meet, Section 307 parr. 1 S. 2 BGB. If, for example, there is a general reference to “human rights” or to an unspecified obligation to “comply with due diligence obligations”, such a wording is likely to be insufficiently clear to the supplier.

Does the GSCCDA require a MCC style – co-responsible – approach to contracting?

As stated in Section 307 parr. 1 S. 1 BGB, GTC clauses should not unreasonably disadvantage the contractual partner. This means that, since the fundamental obligation to implement the GSCDDA and the due diligence obligations lies with the in-scope company, that company must not “pass on” the obligations without first ensuring that their suppliers are also qualified,[26] and taking measures to avoid situations in which their own purchasing practices make it impossible for the supplier to comply with the applicable HRE standards and requirements.[27] A contract that breaches GTC Law becomes at least partially invalid, creating a risk that in-scope companies will fail to obtain the contractual assurances required by the GSCCDA.

In accordance with Section 6 parr. 3 no. 2 the company must avoid contributing to human rights impacts through its procurement or purchasing practices, for example imposing prices that do not allow the payment of reasonable wages or making last minute changes to orders. This obligation, as well as the obligation to seek contractual assurances, need to be implemented in an effective manner, which is defined under Section 6 Parr. 5 GSCDDA, as measures that make it possible to and minimize human rights risks, Section 4 Parr. 2 GSCDDA. As discussed above, the effectiveness of one-sided contracts is questionable. In order to both avoid the risks of falling short of the requirements of not unreasonably disadvantaging counterparts and have effective measures, the safest way is to make use of balanced, shared responsibility approaches to contracting. A good way of doing this is using the public ABA Working Group’s model clauses, which address the buyer’s responsibility to engage in responsible purchasing practices, including by engaging in responsible pricing, modifications, exit, and providing reasonable support to suppliers so that they can carry out HRE due diligence and including their “Buyer Code”[28] as an integral part of the contract.

2) EU Proposal for a Corporate Sustainable Due Diligence Directive

On February 23, 2022, the European Commission published a proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive.[29] Like the GSCDDA, the proposal introduces environmental and human rights due diligence obligations for European and foreign companies meeting certain size and revenue thresholds. The obligations are accompanied by enforcement through national supervisory authorities and civil liability. Contractual measures play a role throughout the proposal, and under Art. 12, the Commission is called upon to develop guidance on voluntary model contract clauses to help in-scope companies to meet the requirements set forth in the proposal.

Contractual measures are part of the due diligence obligations: companies can be required to use them as a means to prevent potential adverse impacts (Art 7 (2)(b)), as well as bringing adverse impacts to an end (Art 8 (3)(c)). For both, the proposal states that companies should use contractual assurances with direct business partners to give legal weight to a company’s code of conduct and help ensure compliance with the code. Such contractual assurances would likely only be required in relationships that are of a certain longevity and intensity and that present a certain level of HRE risk.

Although the proposal applies only to certain large companies, it envisions that due diligence obligations will trickle down to other companies through contractual measures. The contractual measures should include the obligation for the business partner to use contractual assurances with their partners respectively, referred to as contractual cascading. A company may even conclude a contract on due diligence obligations with its indirect partners where relevant to the code of conduct and corrective action plan, though it remains to be seen whether indirect business relationships will have necessary incentives to enter into such obligations. Where necessary, companies need to accompany the measures under Art 7 and Art 8 by developing a prevention or corrective action plan to address concrete risks and adverse impacts in contractual form.

When using contractual assurances, companies need to accompany them by “appropriate measures to verify compliance”, Art. 7 (4) and 8 (5). This can be done through industry initiatives or third-party verification, and the proposal clarifies that such third-party verification needs to be independent, free from conflicts, experienced and accountable for the audit (Art. 3 (h)). In response to the proposal, some have voiced concern[30] that this combination of contractual assurances and verification replicates practices of the past years that have been unsuccessful in their impact but lend themselves to demonstrate that the company took action to address sustainability issues (check-box compliance).

Responsible sourcing practices, i.e. the behavior of the buyer in the contractual relationship are not explicitly mentioned in the Articles of the CSDDD. In light of recital 30, they are however likely covered by the obligation of Art. 7 and 6 to prevent adverse impacts arising from a company`s own operations. Recital 30 explains that taking into account a company`s own pricing and procurement is necessary: “When identifying adverse impacts, companies should also identify and assess the impact of a business relationship’s business model and strategies, including trading, procurement and pricing practices.” As due diligence measures have to be evaluated for their effectiveness under Art. 10, a good means to ensure that contractual assurances and prevention meet this criterion is to include a corresponding obligation regarding responsible purchasing in the contract itself.

Where a company has a relationship with a small or medium enterprise (SME), special provisions highlight that the contractual assurances need to be “fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory” and companies need to bear the costs of verification, Art. 7(4), 8 (5). Though this might not address all the potentially problematic behavior covered by Schedule Q in the ABA MCCs, it does recognize that often, due to an imbalance between the parties, all responsibility and costs for complying with codes of conduct fall on the smaller companies, while the causes of the violations can equally lie with the larger companies.

The proposal clearly provides for the possibility to terminate a contract if the measures fail to bring to an end the adverse impacts. Member states in their national contract law have to provide for such an option (Art. 8 (6)) and companies under Art. 8 (6) (b) should take this measure if the adverse impact is severe. While the recitals state that termination of a contract should be a last resort and may lead to negative consequences, Art. 8 does not explicitly require a company to consider the possible negative effects of terminating a business relationship as part of a “responsible exit”. In light of these requirements, as in the case of the GSCDDA, the safest way to comply is using a shared responsibility approach to contracting, as envisaged by the ABA MCCs.

6. Description of the European Model Clauses (EMC) project

The MCCs provide a good and relevant guideline for improving contractual mechanisms in supply chains. At the same time, the MCCs cannot and should not be implemented in Europe lock, stock and barrel: they were drafted for the US regulatory landscape, which means they are a voluntary tool for (mainly) Buying companies who want to improve their human rights impacts. They do not consider EU mhredd developments such as the proposed EU directive or supply chain due diligence laws from France, Germany and Norway. Additionally, they are based on US contract law and the UN Convention for the International Sale of Goods and might therefore not comply with some requirements set by European (continental) contract law requirements.

To bridge this gap, a European working group has been established to develop European model clauses (EMCs) for supply chains building on the MCCs but adapting them to the European context. On the one hand, this means ensuring they comply with EU law and national contract law systems. Naturally, the European contract law systems and other relevant national legislation vary and, thus, it may be that specific adaptations are required for specific countries. The working group envisages developing general European Model Clauses, also to accommodate the desire of many companies to use comparable clauses in every European country to the extent possible without needing to adapt them for every country. The EMCs will indicate where specific legal systems require specific adaptations.

On the other hand, the EMCs will be situated in a fundamentally different policy setting: if the EU proposal becomes binding, measures to address HRE impacts will not be voluntary anymore and assessing the role of contracts will be an important part of HRE due diligence. The EMCs might therefore be more strictly balanced and substantively prescriptive than the MCCs to ensure their effectiveness and therefore meet the detailed and sanctionable requirements on HRE due diligence set by European mhredd laws.

The first phase of the assessment was a revision of the MCCs to assess which adaptations may be necessary for each European country, bearing in mind that the MCCs should not completely be rewritten. This was undertaken for representative legal systems in Europe: France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and UK. The current members of the working group are reflecting these legal systems and are affiliated with legal practice, academia, and NGOs. The first phase resulted in an assessment of which adaptations to the MCCs are necessary in order to adapt them to the European legal systems.

Currently, the project is in its second phase, where the actual (re)drafting is being done, which includes accommodating deviations in specific legal contractual systems. The second phase will result in a draft of the EMCs with footnotes where necessary indicating exceptions in specific legal systems. In the third phase, a broader European consultation will be held to solicit observations, suggestions, and critique on the clauses. The third phase will result in a first version of the EMCs with footnotes regarding specific legal systems which are ready for implementation.

The European Commission and actors of the European Parliament, who have a specific interest in these model clauses because of article 12 of the Draft CSDDD are being consulted in drafting the Clauses.

Outlook

Contractual language is a mechanism to which companies have turned in practice to address HRE violations in supply chains. Recent legislative developments have built on this practice and included contract mechanisms as part of due diligence obligations of companies. However, contract language will only be effective for improving HRE outcomes if the design incorporates innovative approaches to contract law and addresses the shortcomings of traditional contracting practices. The MCCs and EMCs aim to strengthen effectiveness of contractual mechanisms by integrating a shared responsibility approach, focused on due diligence. More standardization will address the problem of great variety in implementation and content of the clauses. Well-developed Model Clauses therefore hold the potential to make contracts more productive in leading to better HRE outcomes.

Developing sound HRE contractual mechanisms is only a first step, however, and does not in itself guarantee that parties will also effectively enforce them, particularly if the parties do not see a benefit for them in enforcing the clauses or they are concerned about exposing themselves to additional reputational risk.[31] Contractual language alone is also unlikely to change systematic human and environmental rights violations in connection to business practice. As envisaged by the UN Guiding Principles and the OECD Guidelines, contractual clauses are part of a broader due diligence duty and need to be accompanied by other measures.

Due diligence legislation such as an EU Directive and the German Supply Chain law are right to require contractual clauses that oblige suppliers to uphold human rights as one of several measures that companies should take to address these problems. To ensure that they really produce positive outcomes, the CSDDD should specify that they need to be accompanied by contractual obligations for responsible procurement practices by buying companies as well.

[1] See for example Volkswagen, Code of Conduct for Business Partners, accessible at https://www.volkswagenag.com/presence/nachhaltigkeit/documents/policy-intern/2019_Code_of_Conduct_for_Business_Partners-DE-EN.pdf.

[2] See Dadush / Bright / Crispim: Model Contract Clauses to Protect Human Rights in Global Supply Chains (Podcast, 2022), accesible at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XyR3JCRvb38

[3] Accessible at https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf; https://www.oecd.org/corporate/mne/48004323.pdf.

[4] OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, p. 21, accessible at http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-for-Responsible-Business-Conduct.pdf.

[5] See Sect. 6 (4) No. 2 and 4 of the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (GSCCDA) and Artt. 7 (2b; 4) and 8 (3c; 5) of the European Commission`s Draft Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

[6] See https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/?&language=en&content_types=company_responses.

[7] Vaughan-Whitehead / Pinedo Caro, International Labour Office, Purchasing Practices And Working Conditions In Global Supply Chains: Global Survey Results, Inwork Issue Brief No. 10, 11 (2017), p. 6.

[8] Dadush, Prosocial Contracts: Making Relational Contracts More Relational, 85 Law and Contemporary Problems 153-175 (2022), p. 161.

[9] Vaughan-Whitehead / Pinedo Caro, International Labour Office, Purchasing Practices And Working Conditions In Global Supply Chains: Global Survey Results, Inwork Issue Brief No. 10, 11 (2017), p. 7.

[10] Explanatory Memorandum of the German Government for the GSCDDA, BT-Drs. 19/28649, p. 43.

[11] See Lidl`s case study ”Spanish Berry HRIA”, p. 18, accessed at: https://corporate.lidl.co.uk/sustainability/human-rights/hria/hria/spanish-berry

[12] See von Broembsen, Supply Chain Governance – Arguments for worker-driven enforcement, p.6, accesible: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/19402.pdf

[13] OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (2011), Commentary on Chapter 2, para. 22 – accesible at https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/48004323.pdf; UNGP Commentary to Art 19.

[14] Scheltema, The Mismatch Between Human Rights Policies and Contract Law: Improving Contractual Mechanisms in Supply Chains to Advance Human Rights Compliance in Supply Chains, In: Accountability, international business operations, and the law (Liesbeth Enneking e.a. (red.)), Routledge: Londen and New York 2020, p. 259, at 4, accessible at https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Business/WGSubmissions/2018/MartijnScheltema.pdf

[15] These clauses may be accessed at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/human_rights/contractual-clauses-project/mccs-full-report.pdf, see also Snyder / Maslow / Dadush, ”Balancing Buyer and Supplier Responsibilities: Model Contract Clauses to Protect Workers in International Supply Chains, Version 2.0 (April 19, 2021)”. 77 Business Lawyer (ABA) __ (Winter 2021 – 2022), American University, WCL Research Paper No. 2021-15, Rutgers Law School Research Paper No. Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3829782

[16] Principled Purchasing Project, American Bar Association: Model Contract Clauses to Protect Workers in International Supply Chains, Version 2.0 Art. 1.3 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/human_rights/contractual-clauses-project/mccs-full-report.pdf parties to the agreement may also agree on the responsible sourcing practices included in Schedule Q: Responsible Purchasing Code of Conduct: Schedule Q Version 1.0 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/human_rights/contractual-clauses-project/scheduleq.pdf

[17] Principled Purchasing Project / American Bar Association: Responsible Purchasing Code of Conduct: Schedule Q Version 1.0 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/human_rights/contractual-clauses-project/scheduleq.pdf

[18] There are some differences: The GSCDDA focuses mainly on tier 1 suppliers, with tier n suppliers only covered in specific cases; it does not include remediation obligations that Pilar 3 of the UNGP calls for; there is uncertainty if direct linkage relationships create obligations under the GSCDDA or if the obligations are restricted to where a company caused or contributed to a risk. For an overview, see Grabosch/Grabosch, Das Neue Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, § 2 Rn. 15. As the GSCDDA is explicitly oriented on the UNGP, these can, like the ICESCR, the ICCPR, the ILO core conventions and corresponding authorative interpreting decisions by UN and ILO institutions serve as an indicator where the law leaves room for interpretation, see Grabosch/Schönfelder, Das Neue Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, Sect 4 para. 10 f.

[19] in Section 6 para. 4.

[20] Section 6 para. 3 no. 2.

[21] Section 6 para. 4 no. 2.

[22] from Section 3 para. 2.

[23] Explanatory memorandum of the German Government, BT/Drs. 19/28649, p. 49.

[24] Section 7 parr. 2 no. 3, parr. 3 no. 3.

[25] Sherman rightly states this as an implication of HREDD obligations under the UNGPs, BHRJ 2021, p. 127, 132 et seq.. As the GSCDDA are based on the UNGP they can serve as a source to interpret them if the GSCDDA did not consciously diverge from them, Grabosch/Grabosch, Das Neue Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, Sect. 2, para. 15.

[26] Grabosch/Grabosch, Das Neue Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, Sect. 5, para. 95; see also the on the need to take into account the interests of the counterpart Wagner in Wagner / Ruttloff / Wagner, Das Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz in der Unternehmenspraxis, Sect. 14, para. 2147.

[27] Spindler, Verantwortlichkeit und Haftung in Lieferantenketten – das Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz aus nationaler und europäischer Perspektive, ZHR 2022, 67 (106).

[28] https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/human_rights/contractual-clauses-project/scheduleq.pdf.

[29] available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/proposal-directive-corporate-sustainable-due-diligence-and-annex_en. For an overview of the obligations and the enforcement, contrasted with the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act and the French Loi de Vigilance, see Brabant / Bright / Neitzel / Schönfelder: Due Diligence Around the World: The Draft Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (Part 1), VerfBlog, 2022/3/15, https://verfassungsblog.de/due-diligence-around-the-world/ and Brabant / Bright / Neitzel / Schönfelder: Enforcing Due Diligence Obligations: The Draft Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (Part 2), VerfBlog, 2022/3/16, https://verfassungsblog.de/enforcing-due-diligence-obligations/

[30] The Danish Institute for Human Rights: Legislating for Impact analysis of the proposed EU corporate sustainability due diligence directive, (2022), accessible at https://www.humanrights.dk/publications/legislating-impact-analysis-proposed-eu-corporate-sustainability-due-diligence, p. 19.

[31] One way to incentivize enforcement would be to include express third-party beneficiary rights, as tested in the US, see Ryerson: CAL Victory: Test Case Offers Solution for Global Worker Exploitation, Corporate Accountability Lab, (2018), https://corpaccountabilitylab.org/calblog/victory-test-case-offers-solution?rq=victor.

Suggested citation: D. Schönfelder, B. Braun and M. Scheltema, ‘Contracting for human rights: experiences from the US ABA MCC 2.0 and the European EMC projects’, Nova Centre on Business, Human Rights and the Environment Blog, 1st November 2022.

Latest Posts

Categories

- Annual Conference on Business; Human Rights and Sustainability

- Blogging on B&HR: Towards an EU CSDDD

- Business and Human Rights Developments at the European Level

- Business and Human Rights Developments in Central and Eastern Europe

- Business and Human Rights Developments in Southern Europe

- Business and Human Rights in Conflict

- Business and Human Rights in the World

- Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

- Exploring new frontiers in the updated OECD Guidelines

- Latest Business and Human Rights Developments

- National Contact Points for Responsible Business Conduct: the road ahead for achieving effective remedies

- Notícias sobre Empresas e Direitos Humanos

- Second Annual Conference on Business; Human Rights and Sustainability

- Serie de blogs “Explorando los caminos hacia el acceso efectivo a la justicia en materia de empresas y derechos humanos”

- Short-Termism in Business Law: A Global Approach

- Sustainability Talks

- Young Voices and Fresh Perspectives