Gabriella Gutemberg holds a Bachelor of Laws, LL.B at Cândido Mendes University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She is also a postgraduate in Human Rights at CEI Course, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and a master’s student in Law and Technology at NOVA School of Law, Lisbon, Portugal.

Ana Gabriela Godoy Brandão holds a bachelor of Laws, from Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Brazil. She is a specialist in Criminal Law at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil and a specialist in Human Rights and Regional Realities, Unicesumar, Brazil. She is also Master’s student at NOVA School of Law, Lisbon, Portugal.

Gabriela Quevedo is a Lawyer from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, a Licence Attorney in Microsoft Chile, and holds a degree in Law and Tech from the Universidad Complutense Madrid. She is currently a master’s student in Law and Management at NOVA School of Law, Lisbon, Portugal. She is also an Attorney at Chambers of Commerce Chile Portugal.

Luna Zehner holds a Bachelor of Laws, LL.B. at Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium. She is a Master of Laws, LL.M. Corporate track at Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium and was an Erasmus student at NOVA School of Law, Lisbon, Portugal. She is also an Associate at MOORE Belgium Tax and Legal Services, Business Legal.

Proposal for a Directive on equal pay for equal work and pay transparency

Since 1957, primary European law requiring equal pay for equal work between men and women has been put forward. This means that there has been a framework for equal treatment between the genders in light of employment law for over 55 years. However, the gender pay gap currently still stands at 14,1%, which is unacceptably large.

For this reason, the European Commission has issued a proposal for a directive, which focuses on two core principles of equal pay. First, the proposal lays down measures that ensure pay transparency for workers and employers, and secondly, it aims to provide victims of pay discrimination better access to justice.

The primary legal bases to this proposed directive can be found in the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), namely article 19(1) and article 157(3) of the TFEU. The former article combats discrimination based on gender, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age, or sexual orientation. The latter ensures the application of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation, including the principle of equal pay for equal work or work of equal value.

Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament, on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (the Recast Directive), forms the main legal basis of the new proposed directive on pay transparency, as well as the 2014 Commission’s Recommendation on pay transparency (2014 Recommendation). Unfortunately, these turned out to be insufficient to make the gender pay gap disappear in the Union.

The proposal was issued on the 4th of March 2021, a year after the massive coronavirus outbreak worldwide. Which, to me, is not a coincidence. The legacy of this pandemic cannot be allowed to result in less equal pay, in particular if we consider the high concentration of female workers in essential and front-line medical sectors (76% of the 49 million care workers in the EU are women). Their crucial role during the pandemic called for a systematic re-evaluation of their pay, which will hopefully result in proper appreciation and payment for their work.

Child penalty

Considering all the measures aimed at ensuring the application of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women, in matters of employment and occupation, the question is why does the gender pay gap remain.

Women have overcome many grounds for discrimination. They continue to be treated as the primary caregivers of children, and one cannot talk about equal opportunities and equal treatment without first recognizing the effects of children on the women’s careers in comparison to men.

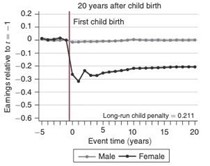

Kleven et al. (2019) presents this scenario by analysing Danish administrative data from 1980-2013 and, although the study is focused on a Denmark perspective, quite often could be applicable worldwide.

According to them, the arrival of children creates a gender gap in earnings of around 20% in the long run and, as a result, almost all the remaining gender inequality can be attributed to children. The proof of this theory is evidenced when men’s and women’s careers are compared. It is possible to see that the parents are equally involved until the baby’s birth, move away drastically immediately after the baby’s birth, and never converge again. They define this as the “child penalty” which is represented by the percentage in which women fall behind men due to the children’s arrival:

(Kleven et al., p. 40)

(Kleven et al., p. 40)

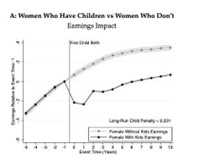

Another striking finding from this analysis is that child penalties are gradually taking over as the main cause of gender inequality, because when the comparison is made between a woman’s career with children to the other woman’s career without children, discrimination is not related to the gender anymore, but to the condition of being a mother or not:

(Kleven et al., p. 44)

(Kleven et al., p. 44)

According to The Global Gender Gap Index 2021, the 10 countries that narrowed the gender gap the most in the last year were Iceland, Finland, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Namibia, Rwanda, Lithuania, Ireland, and Switzerland.

Many factors can interfere with these positions. Still, the resurgence of the conservative debate on abortion, associated with centuries of women’s incapacity to make their own decisions about their bodies, sheds light on perhaps the most important point to consider at this time of the debate: how essential it is for women to be able to legislate for their own causes.

The percentage of women in parliament in these “top 10 countries” are the highest rates worldwide. The possible reasons that led Iceland to keep its number one spot in the 2021 edition for the 12th year in a row can be attributed to the fact that they elected the world’s first female president in 1980, and the number of women in the Icelandic parliament gradually increased during those years, until it got one of the highest rates in the world as we saw (47.6 % in 2021). Consequently, the country has spent many years legislating in favour of women, including making laws that are completely avant-garde when compared to the rest of the world.

As an example, the Act on Maternity/Paternity Leave and Parental Leave No. 95/2000 grants equal paid leave to men and women, with the aim of ensuring that the child has access to both parents and that both of them have the same opportunity to reconcile work and family. By doing this, it does not matter whether the employer will hire a young man or a young woman because, likewise, the possibility of parental leave for both will have to be considered. Also, it allows child-related tasks to be better divided.

Gender pay gap app

The gender pay app was created after the 2018 Corporate Governance Code stated that companies with 250 or more employees must calculate the difference in earnings. The app organised the data and published it for everyone to see the actual data from every company. The truth is that even though a lot of companies are fighting this inequality, some showed a huge divergence.

At Manchester City Football Club, for example, the average hourly wage earned by women is 86.6% lower than that of men. At the British Airways airline, the rate is not so high, but it is striking that women earn 53.6% less, on average per hour worked, than men.

To make the submission, the employer must follow some requirements defined by his own government, who offer guidance explaining the data the employers must gather and how the calculations have to be made in order to be as fair and relatable as possible.

Thus, the employers must calculate, report, and publish this gender pay gap figures:

- percentage of men and women in each hourly pay quarter;

- mean (average) gender pay gap using hourly pay;

- median gender pay gap using hourly pay;

- percentage of men and women receiving bonus pay;

- mean (average) gender pay gap using bonus pay;

- median gender pay gap using bonus pay.

Differences in payment are caused by occupational segregation, which means there are more men in higher-paid industries and women in lower-paid industries. We can see this with the financial industry where 61% of the workers are men. However, women rule 78% of the health and social work industries, areas that got an added value after 2020 after the pandemic covid 19 struck.

The second type or cause of discrimination is called vertical segregation, where fewer women are in senior, and hence better-paying positions. It gets even more shocking when analysing the more innovative or growing markets in the finance industry for instance. Here, among senior roles in venture capital (VC) firms, only 4,9% of the partners are female.

The picture doesn’t get much better when it comes to private equity (PE), in which fewer than 10% of senior roles are held by women. This vertical segregation also has an influence or an aspirational side, with fewer women in these roles, it is harder for other women to think of advancement in a company and, as a consequence, to negotiate their salaries, ask for a raise, or to apply for a better position.

The responsible investment groups have spent years working to improve gender diversity among senior decision-makers at listed companies. While these efforts have been related to positive, trendy, fashionable and financial outcomes, to date they are yet to make a significant reduction in the key issue of gender pay gaps. Initiatives such as this public information and shout-out, help society get more involved.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Pb. L. 26 October 2012, afl. 326, 1.

- Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 5 July 2006 on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (recast), Pb. L. 26 July 2006, afl. 204, 23.

- 2014/124/EU: Commission Recommendation of 7 March 2014 on strengthening the principle of equal pay between men and women through pay transparency, Pb. L. 8 March 2014, afl. 69, 112.

- Proposal (Comm.) for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council to strengthen the application of the principle of equal pay for equal work or work of equal value between men and women through pay transparency and enforcement mechanisms, 4 March 2021, COM(2021) 93 final – 2021/0050 (COD).

NUMHAUSER-HENNIG, A., “EU Equality Law – Comprehensive and Truly Transformative?” in RÖNNMAR, M. (ed.), Labour Law, Fundamental Rights and Social Europe, 2011, 286 p. - EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY RESEARCH SERVICE, “Equal pay for equal work between men and women: Pay transparency and enforcement mechanisms (EU legislation in progess)”, 21 February 2022 via https://epthinktank.eu/2022/02/21/equal-pay-for-equal-work-between-men-and-women-pay-transparency-and-enforcement-mechanisms-eu-legislation-in-progress/

- H. KLEVEN, C. LANDAIS, J. SØGAARD, “Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence From Denmark”, 31 March 2021 via https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24219/w24219.pdf

- WORLD POPULATION REVIEW, “Gender Equality by Country 2022”, 31 March 2021 via https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gender-equality-by-country

- STATISTA, “Share of women in the Icelandic Parliament from 1974 to 2021”, 31 March 2021 via https://www.statista.com/statistics/1090585/share-of-women-in-the-icelandic-parliament/

- WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM, “Global Gender Gap Report 2021”, 31 March 2021 via https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf

- INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION, “Women in Parliament in 2021”, 31 March 2021 via https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/reports/2022-03/women-in-parliament-in-2021

- Act on Maternity/Paternity Leave and Parental Leave, No. 95/2000, 31 March 2021 via https://www.government.is/media/velferdarraduneyti-media/media/acrobat-enskar_sidur/Act-on-maternity-paternity-leave-95-2000-with-subsequent-amendments.pdf

Suggested citation: G. Gutemberg, A. G. Brandão, G. Quevedo e L. Zehner, ‘Gender Pay Gap’, Nova Centre on Business, Human Rights and the Environment Blog, 14th November 2022.

Latest Posts

Categories

- Annual Conference on Business; Human Rights and Sustainability

- Blogging on B&HR: Towards an EU CSDDD

- Business and Human Rights Developments at the European Level

- Business and Human Rights Developments in Central and Eastern Europe

- Business and Human Rights Developments in Southern Europe

- Business and Human Rights in Conflict

- Business and Human Rights in the World

- Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

- Exploring new frontiers in the updated OECD Guidelines

- Latest Business and Human Rights Developments

- National Contact Points for Responsible Business Conduct: the road ahead for achieving effective remedies

- Notícias sobre Empresas e Direitos Humanos

- Second Annual Conference on Business; Human Rights and Sustainability

- Serie de blogs “Explorando los caminos hacia el acceso efectivo a la justicia en materia de empresas y derechos humanos”

- Short-Termism in Business Law: A Global Approach

- Sustainability Talks

- Young Voices and Fresh Perspectives