About the authors:

Michelle Baxter Wickham is a Private Sector Engagement Manager at World Animal Protection, engaging with the private sector to transform the food system. World Animal Protection is a global animal protection organisation that has been moving the world to protect animals for more than 70 years. They collaborate with local communities, the private sector, civil society, and governments to change farmed and wild animals’ lives for the better. Prior to joining World Animal Protection, Michelle worked in the private, public, and civil society sectors to positively impact the lives of both animals and humans.

Katie Arth is the Director of Global Engagement in the Farm Animal Welfare and Protection department at Humane Society International. She uses her 15+ years of experience in the animal protection movement to work with country teams and companies to implement animal welfare policies. Advancing the welfare of animals in more than 50 countries, Humane Society International works around the globe to promote the human-animal bond, rescue and protect dogs and cats, improve farm animal welfare, protect wildlife, promote animal-free testing and research, respond to natural disasters and confront cruelty to animals in all its forms.

Sophie Aylmer is the Head of Policy for Farm Animals and Nutrition at FOUR PAWS, a global animal welfare organisation for animals under direct human influence, which reveals suffering, rescues animals in need and protects them. FOUR PAWS focuses on companion animals, farm animals and wild animals kept in inappropriate conditions as well as in disaster and conflict zones. Sophie has worked in public policy, including for the European Union, and civil society for over 10 years, advocating for a world where the environment and all animals and people are protected

This blog symposium is co-organised by OECD Watch and NOVA School of Law.

Earlier this year, the updated OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (Guidelines) were adopted. These Guidelines include, for the first time since their inception in 1976, a clause on animal welfare, which has the potential to transform the lives of billions of animals. It states:

“Enterprises should respect animal welfare standards that are aligned with the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) Terrestrial Code. An animal experiences good welfare if the animal is healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, is not suffering from unpleasant states such as pain, fear and distress, and is able to express behaviours that are important for its physical and mental state. Good animal welfare requires disease prevention and appropriate veterinary care, shelter, management and nutrition, a stimulating and safe environment, humane handling and humane slaughter or killing. In addition, enterprises should adhere to guidance for the transport of live animals developed by relevant international organisations.” (Chapter 6, Paragraph 85).

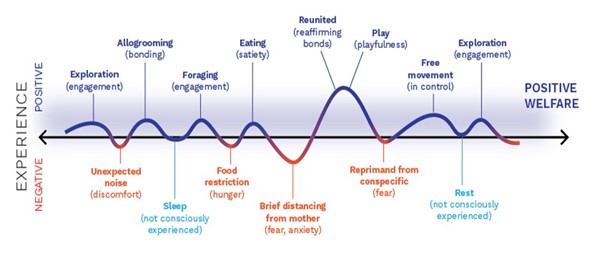

The WOAH definition of animal welfare encompasses the Five Freedoms (which focus on the absence of negative states – freedom from hunger and thirst; freedom from fear and distress; freedom from discomfort; freedom from pain, injury, and disease; and freedom to express normal behaviour) and the more up-to-date Five Domains model (which emphasises the provision of positive states relating to sufficient and species-specific nutrition; environment; health; behaviour; and mental state). Both are tools to understand animal welfare rather than standards that companies and governments should follow. It is widely accepted that animals can experience a life not worth living; a life worth living; and a good life. Our assertion is that all policy-makers and decision-makers should be striving for the latter.

Diagram by the Zoo and Aquarium Association (ZAA) showing that animal welfare is a continuum and how positive and negative experiences can impact an animal’s physical and mental state.

Numerous animal protection organisations, including FOUR PAWS, Humane Society International, and World Animal Protection campaigned for the OECD to specifically include animal welfare in the revised Guidelines. Overall, we are pleased with the result as it should reduce the suffering that animals endure. Do we wish that the language was stronger? Yes. Are we concerned that member states and multinational enterprises will continue to do the bare minimum? Of course. However, the Guidelines now give us a mechanism in which to hold both to account.

Animals used by industry

From corporate food procurement to global and local tourism, animals are part of countless businesses and their value chains.

Approximately 92 billion land animals and 500 billion aquatic animals are farmed for food each year, the majority of whom are kept in industrialised production systems that cause immense suffering. Animals experience stress and pain due to selective breeding, severe confinement, and mutilations without anaesthetic, amongst myriad other welfare issues.

Animal use in fashion is also big business, with more than 100 million animals killed annually for their fur alone and 3.4 billion ducks and geese slaughtered for down and feathers. Despite the growing number of viable alternatives to animal-derived materials on the market, many fashion brands continue to use animals without ensuring their welfare. Animals are trapped from the wild or bred on farms, kept in overcrowded cages or sheds, and often skinned alive, beaten to death or electrocuted so as not to damage their skins or feathers.

The entertainment industry also causes animal suffering, in the captive display of wild animals in roadside zoos, for lions bred for trophy hunting, in elephant feeding/bathing/riding experiences, and in dolphin exhibits, among other contexts. These animals are removed from their natural environments, or born into captivity, and forced to perform unnatural behaviours. They are trained using techniques based on fear and pain, and often caged or chained. Wild animals exploited by the global pet, food, and traditional medicine trades suffer similar fates. It is difficult to put a figure on the total number of animals traded but the legal wildlife trade, including timber and fisheries, generates over $300 billion per annum.

Risks of poor animal welfare

The Guidelines’ inclusion of animal welfare supports its growing presence in mainstream environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and sustainability conversations. The risks of ignoring animal welfare fall into three main categories: reputational, operational, and societal.

Although animals are scientifically recognised as sentient beings, in animal agriculture they are treated as units of production. As a result, standard industry practices such as breeding animals for higher yields and the adoption of intensive confinement systems including battery cages, colony cages, gestation crates, and farrowing crates have highly detrimental effects on their health and welfare.

Animals may have poor welfare on farms of any size, but most operations supplying multinationals are large-scale, intensive operations that use crowded, barren confinement facilities. Animals may be transported over long distances between production sites or to slaughter, where they experience fear, distress, and intense pain, depending on the species and method used.

Reputational risks

More than 2,000 major food companies, including McDonald’s, Marriott, Conagra, Compass Group, and Aramark, have pledged to eliminate eggs and/or pork from caged animals in their supply chains. Those that have not made the switch have been subject to damaging public information campaigns. In 2023, animal welfare campaigners engaged in a multi-country campaign targeting Jollibee, the largest restaurant chain in Asia. After four months of protests and digital campaign actions the company published a commitment to stop using eggs from caged hens, which is an important first step to improving welfare for some of the animals in their supply chain.

Operational risks

Companies that do not comply with the Guidelines, ensuring or enhancing animal welfare standards in their supply chain, now can face formal complaints to the OECD governments’ National Contact Points (NCPs). If mediation facilitated by an NCP leads to an agreement, companies could, among other measures, make an apology to their consumers for bad animal welfare practices in the past or improve their policies and practices, as well as those of their suppliers, by using mandatory contractual provisions on ensuring good animal welfare. Additionally, when companies refuse to engage in improving animal welfare, they are at risk of traditional campaigns and investigations. Most civil society organisations (CSOs) prefer to have meaningful dialogue with key players and to support companies in taking action to improve welfare instead of going down a more negative route.

It is also an operational risk for companies to only address animal welfare shortcomings once dictated by the law. A growing number of countries have enacted farmed animal welfare laws, directives, and regulations. The trend toward legislating higher welfare is clear, for instance, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Bhutan, Norway, and 11 states in the United States of America have banned or are phasing out the use of battery cages. Austria, Germany, and Switzerland have banned cage systems entirely for laying hens. The European Union prohibits keeping sows in gestation crates for more than 28 days. In 2018, California passed Proposition 12, prohibiting the sale of animal products produced using cages for hens or gestation crates for pigs. On the other hand, some countries have done little to nothing, leaving a patchwork of policies for multinational companies to contend with. Wise companies are adopting their own strong animal welfare policies, which put animals first, by going above and beyond outdated laws to streamline efficiency and avoid having to play “catch-up” with new legislation. For example, companies had 5 years to implement crate-free systems for mother pigs with Proposition 12, but many producers that sell in California are now rushing transitions because they had hoped that failed legal challenges would stop the implementation of the law.

Sustainability reporting standards, including the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), and the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) are increasingly including animal welfare as a reporting metric by financial institutions when they do their due diligence for loans. The ISSB states “Consumer demand has driven shifts in industry practices, such as eliminating the use of gestation crates in hog production and eliminating caged enclosures for poultry.” If a company wants financing for new projects, they are going to be asked questions about the company’s plans to eliminate antiquated and cruel systems that consumers no longer support. Such benchmarks not only report, but also help to improve, standards by bringing transparency to what companies are doing, or not as the case may be, and creating a race to the top for those that want a competitive edge.

Societal risks

When it comes to large-scale animal agriculture, most current production practices are designed to maximise profit over animal welfare. In addition to packing as many animals as possible into a facility through intensive cage confinement or producing animals that grow so fast their bodies cannot withstand their own weight, the impact of so many animals in one location or in one region can create more pollution than the environment can absorb, resulting in the degradation of land and water systems, and human health concerns. Further, with production systems untouched, we can expect an increase in the number of animals kept due to a growing population and demand for meat in the Global South, even though research indicates that animal agriculture is responsible for at least 16.5% of all global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

Next steps for the OECD, governments, and multinational enterprises

OECD and governments

Due to the complexity of the issue, the OECD should develop and publish evidence-backed guidance for companies on animal welfare standards, like it has done for specific sectors and risk issues, as well as at a cross-sectoral level through the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct. When developing such guidance, it must continue its good practice of consulting and closely engaging with all stakeholder groups, including animal welfare organisations and civil society experts, to gather crucial perspectives and further build on the progressive text now embodied in the Guidelines. The guidance would also clarify and explain to enterprises their role and responsibilities under the updated Guidelines.

Civil society welcomes the opportunity to work with the OECD, governments, and NCPs to offer training programs, workshops, and capacity-building initiatives to help governments, NCPs, and enterprises improve their understanding of animal welfare issues and ensure proper implementation of related laws. Animal welfare problems are an issue in every country, but priority issues may vary based on the country’s top industries and the current legislative landscape. For example, a top egg-producing country may need to address battery cages while a country that is investing in aquaculture may need to address fish welfare.

We also look to OECD states to ensure that businesses are aware of the new standards in the Guidelines and the consequences for poor animal welfare in their own activities as well as in their supply chains. Governments should proactively and meaningfully raise enterprises’ awareness of this critical issue.

Multinational enterprises

Multinationals with complex supply chains may not have a full view of how animals are being used in their businesses. The first step for these enterprises is to recognise that they now have responsibilities to ensure good animal welfare in their own operations, as well as the activities of companies with which they conduct business. As set out in the Guidelines and OECD Due Diligence Guidance, enterprises should conduct due diligence to assess how they use animals, as food products, for clothing, testing for cosmetics, etc. and if they may be linked to poor animal welfare practices. If they are, they should stop, prevent, or mitigate these harms and in some cases provide for or cooperate in remediation of these harms. This should involve considering whether there is a more humane and sustainable way for the company to operate, such as using fewer animals, striving for high welfare, or diversifying their portfolio to include plant-based or synthetic options. At a minimum, companies should adopt and implement good animal welfare policies in alignment with the WOAH definition referenced in the OECD Guidelines.

People working in procurement, sustainability, and other corporate departments tasked with overseeing animal welfare are encouraged to contact global and local CSOs that can help provide expert guidance which aligns with the most up to date science-based animal welfare recommendations and the current legal landscape.

Conclusion

The strong corporate standards on animal welfare in the Guidelines must be implemented by companies. Companies that fail to meaningfully address poor animal welfare within their supply chains face material risk and return implications. Many standard practices violate the WOAH animal welfare definition.

The standards in the Guidelines also need to move from just voluntary recommendations to enforceable regulation enacted by governments, with the OECD and multinationals engaging on this topic to make change for animals. While important progress has been made, it is time to go further. The Guidelines can play a key role in encouraging good practice by enterprises and in their value chains now, and also in shaping policy and law promoting good animal welfare in the future.

Suggested citation: M. B. Wickham, K. Arth and S. Aylmer, ‘The updated OECD Guidelines and animal welfare: From recognition to reality’, Nova Centre on Business, Human Rights and the Environment Blog, 15th November 2023